Inside the Blue Line

1997-2001

Several things attracted me to the idea of photographing within New York’s Adirondack Park. At over six million acres, it is the largest nature preserve in the lower forty-eight states, and one of the oldest. And perhaps nowhere else can one so accurately track the changes in the ethics of land use.

In pre-colonial times, the Haudenosaunee used the Adirondacks mainly for hunting because they deemed the region too harsh and barren for year-round living. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition reached the Pacific coast in the early 1800s, the Adirondacks had been little explored by Europeans. But by mid-century, painters and writers had begun to romanticize the rugged landscape and its inhabitants, and the region grew increasingly popular as a tourist destination.

In the 1880s, extensive clear-cutting of forestlands prompted the New York State Legislature to create the Adirondack Forest Preserve. The state established the Adirondack Park in 1892, incorporating the public Forest Preserve and private lands surrounding it. Three years later, voters amended the state Constitution to declare the Forest Preserve “forever wild.” Because the Adirondack Park’s original boundaries—designated on a map by a blue line—included public and private land, an uneasy alliance was created that continues to test individual and collective ideas regarding land management and preservation.

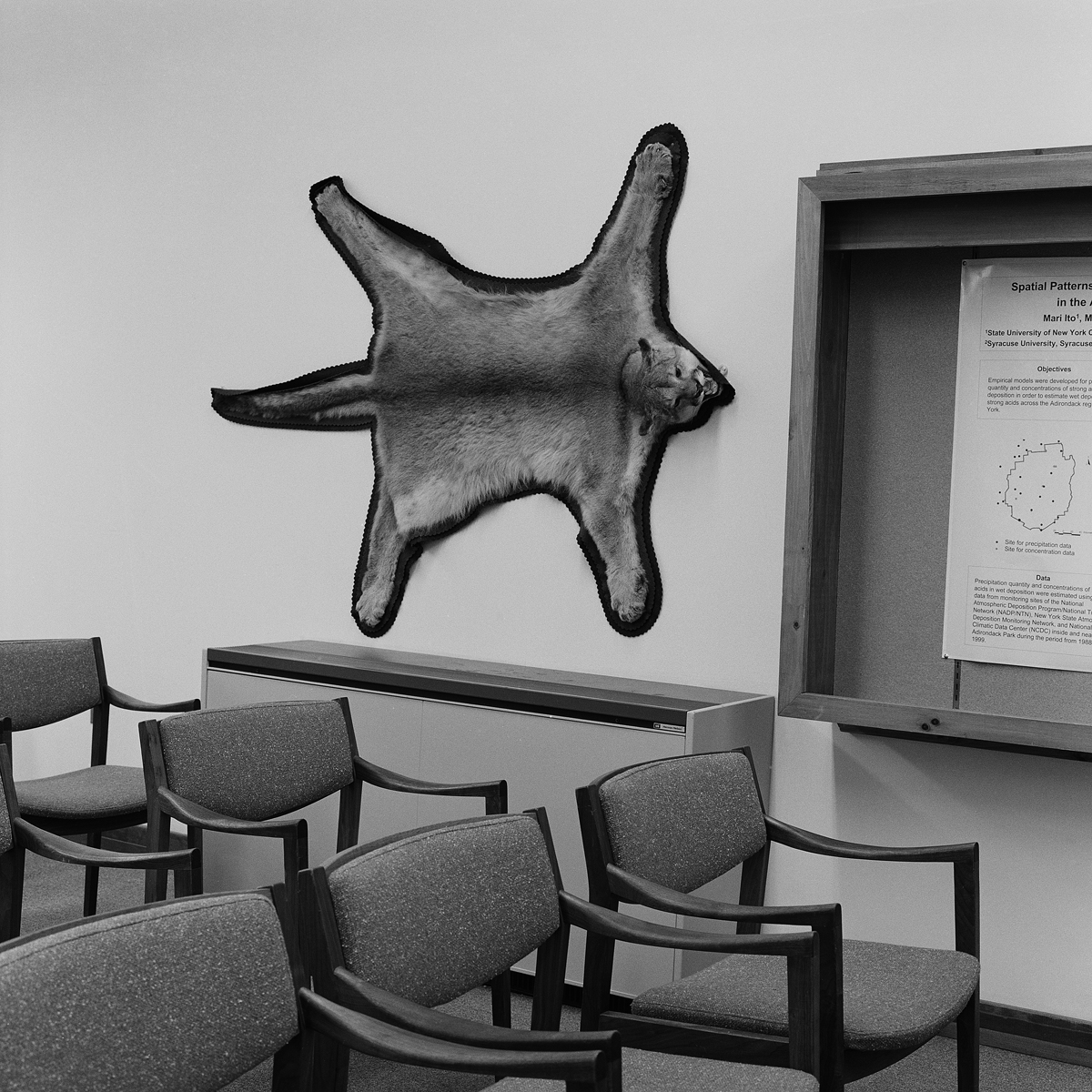

These photographs refer to and have been inspired by the Adirondacks and its history, but only to serve a broader narrative—that of our irresolute response to the persistence of nature. In resisting the urge to “tell the story” of the Adirondacks, I found visual situations that resonate on multiple levels--pictorially, contextually, and poetically – images that speak to how we experience and contend with nature.